Demystify Therapeutic Diets

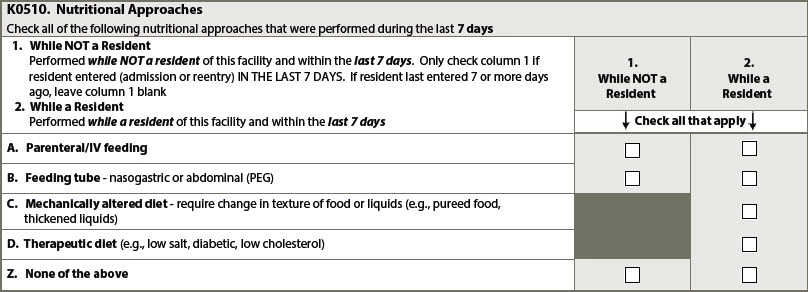

Knowing these commonly used terms will help you better navigate compliance. So, what’s the deal with therapeutic diets anyway? The term comes up frequently, alongside weight gain or weight loss, as well as a few other prescribed diets. What should facility teams be doing to manage and document therapeutic diets, especially since the staff involved span multiple departments? Keep reading for information on the most important definitions, what you need to know for documentation, and how to remain compliant. The resident’s care and well-being is, of course, the priority. Know These Definitions Weight gain and weight loss are standards that affect some quality measures for facilities, and obviously affect individual residents. Although weight gain or weight loss can be a marker of significant change and, thus, trigger additional assessments, it’s important to balance the resident’s bodily needs and clinical condition against their quality of life, which may be affected by how they receive nutrition. Here are some definitions and guidance from pages K-8 through K-11 of the CMS Long-Term Care Facility Resident Assessment Instrument (RAI) 3.0 User’s Manual often referred to as the MDS Manual or the RAI Manual: 5% Weight Gain In 30 Days: Start with the resident’s weight closest to 30 days ago and multiply it by 1.05 (or 105%). The resulting figure represents a 5% gain from the weight 30 days ago. If the resident’s current weight is equal to or more than the resulting figure, the resident has gained more than 5% body weight. 10% Weight Gain In 180 Days: Start with the resident’s weight closest to 180 days ago and multiply it by 1.10 (or 110%). The resulting figure represents a 10% gain from the weight 180 days ago. If the resident’s current weight is equal to or more than the resulting figure, the resident has gained more than 10% body weight. Parenteral/IV Feeding: Introduction of a nutritive substance into the body by means other than the intestinal tract (e.g., subcutaneous, intravenous). Feeding Tube: Presence of any type of tube that can deliver food/ nutritional substances/ fluids/ medications directly into the gastrointestinal system. Examples include, but are not limited to, nasogastric tubes, gastrostomy tubes, jejunostomy tubes, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tubes. Mechanically altered diet: A diet specifically prepared to alter the texture or consistency of food to facilitate oral intake. Examples include soft solids, puréed foods, ground meat, and thickened liquids. A mechanically altered diet should not automatically be considered a therapeutic diet. Therapeutic diet: A therapeutic diet is a diet intervention ordered by a health care practitioner as part of the treatment for a disease or clinical condition manifesting an altered nutritional status, to eliminate, decrease, or increase certain substances in the diet (e.g., sodium, potassium) (ADA, 2011). Code Means of Alternative Nutrition A resident’s nutrition-delivery method should be recorded on the MDS, specifically in item K0510 (Nutritional Approaches). The lookback for this item is 7 days — and your answers will depend on whether the resident was admitted or readmitted in that period. Refer to the definitions above for more information on the subitems for K0510. The RAI Manual notes that how a resident receives nutrition can boost their clinical condition but may diminish their sense of dignity or the pleasure they take in meals. “It is important to work with the resident and family members to establish nutritional support goals that balance the resident’s preferences and overall clinical goals,” the RAI Manual says, on page K-10. Additionally, staff should monitor the resident’s nutritional approach for effectiveness, as well as periodically reevaluating the care plan to ensure that a particular approach continues to be appropriate. Keep These Points in Mind for Compliance Surveyors can hit you with citation F808 for issues with therapeutic diet prescription. Surveyors are looking to see that a resident’s diet is appropriate for their health, as well as evidence that the diet was prescribed by a practitioner for medical purposes. Although the language in the Appendix PP of the State Operations Manual specifies “physician,” it also notes that physician can, in this case, encompass physician assistant, nurse practitioner, and clinical nurse specialists involved in the resident’s care. According to the regulation for F808, therapeutic diets must be prescribed by the attending physician, although the physician can delegate the task of prescribing the diet to a registered or licensed dietician (if allowed by the state), says Linda Elizaitis, RN, RAC-CT, BS, president and founder of CMS Compliance Group in Melville, New York. In this situation, the physician must still supervise the dietician, Elizaitis notes, and modify a diet order if necessary. Although the documentation of who prescribes what kind of diet when is important, everything comes down to a facility’s organization in the kitchen. Elizaitis describes some recent situations where facilities received immediate jeopardy citations: One where a resident liked grilled cheese sandwiches and the registered nurse overseeing the meal provided the sandwich instead of the physician-prescribed ground meats only diet the resident was supposed to get. Another immediate jeopardy citation was levied against a facility when a surveyor observed a resident spit out pieces of chicken and chicken skin, and, upon inspecting the tray ticket, saw that that resident was supposed to have a ground diet. “Both of these actual citations provide a strong reminder about the importance of ensuring that there is a system in place for tray accuracy and that responsible staff receive education about their responsibilities,” Elizaitis says. Facilities need proper systems in the kitchen to monitor meal tray assembly and make sure that whatever a resident is being served matches their respective ordered diet — and actually makes it on the meal tray and to the resident, she says. “Nursing is not off the hook — there should be a system in place for validating that the food/fluids served to each resident is consistent with the ordered diet as well as addressing any fluid restrictions,” she says. In short, everyone should be reading the meal tickets. Err on the Side of Education Make sure staff have the knowledge they need to understand the significance of each resident’s diet being correct. If Mr. Jones is supposed to get a hamburger with ketchup and Mrs. Lee is supposed to get a hamburger with mustard, it’s no big deal, but residents who have trouble swallowing or are at increased risk of aspiration can meet bad outcomes from meal mix ups. Making sure staff in the kitchen and in nursing units understand the clinical context surrounding altered diets and fluid restrictions can help them know how to assemble a meal tray and check for accuracy, Elizaitis says. Facilities and management should be assessing staff knowledge through observation regardless of when surveyors come knocking.