Consider Complete Picture, Correctly Code This Celiac Case

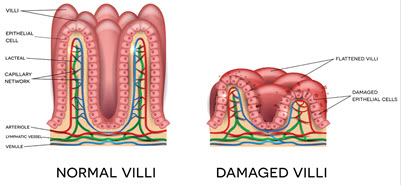

Also: See whether the encounter levels best with MDM or time. You’ve probably seen several claims related to celiac disease, but that doesn’t mean you’re confident about coding it. You must rely on thorough documentation while also making sure you’re submitting all the correct details and appropriately leveling the encounter to avoid denials. Whether your celiac coding skills need some work, or you’re just trying to get a handle at better documenting the disease, take a look at this case study to strengthen your skills. The case: A 16-year-old established patient presents to the pediatrician complaining of abnormal weight loss, frequent bloating, and excessive flatulence, and is currently also experiencing functional diarrhea. The medical record shows a family history of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), celiac disease, and a previous dermatitis herpetiformis diagnosis that resulted in a rash that has yet to resolve. The clinician ordered serology antibody testing due to suspected celiac disease, but test results are not yet available. As a precaution, the provider started the patient on a strict gluten-free diet and a prescription for the itchy rash. The entire encounter took 25 minutes. Consult These Symptoms and History Codes There is no definitive diagnosis at this point because the blood test results are pending. This means you must code the information that is available at this encounter. Symptoms: According to ICD-10 Official Guidelines, Section I.B.4, you’ll code the signs and symptoms “when a related definitive diagnosis has not been established (confirmed) by the provider.” According to the notes from the encounter, these are the patient’s symptoms: History: In addition to symptoms that the physician records during the exam, the patient’s personal and family history helps the provider assess the likelihood of celiac disease. As you know, a complete personal, family, and social history (PFSH) is no longer a requirement for determining an office/outpatient evaluation and management (E/M) level, but these details are still pertinent pieces of the patient’s medical record going forward. In this case, there is a family history of both IBS and celiac disease. All of these factors, including the signs and symptoms, support the possibility of celiac disease and will help prove medical necessity for the blood test. There is no specific code for family history of celiac disease or IBS, so you’ll need to report Z83.79 (Family history of other diseases of the digestive system). You know this is the correct code for both because of the note underneath the parent code Z83.7 (Family history of diseases of the digestive system), which says, “Conditions classifiable to K00-K93.” The codes K58.- (Irritable bowel syndrome) and K90.0 (Celiac disease) fall within that range. Coding alert: If the provider ends up diagnosing the patient with celiac disease at a subsequent visit, pay attention to the Use additional note under the code in ICD-10 that instructs you to report L13.0 (Dermatitis herpetiformis) and/or G32.81 (Cerebellar ataxia in diseases classified elsewhere) if applicable. The patient does have dermatitis herpetiformis, which is a chronic, itchy rash made up of bumps and blisters that manifest on the skin of some people who have celiac disease. Level the Encounter Using MDM or Time To level this encounter, you’ll need to decide whether to calculate using medical decision making (MDM) or time. Remember, you always want to choose based on which method most accurately represents the care provided. For this encounter, you’ll select from the established patient office/outpatient E/M code set: 99212-99215 (Office or other outpatient visit for the evaluation and management of an established patient…). In the case study, the teenager presents with diarrhea, weight loss, bloating, and abnormal flatulence, as well as unresolved dermatitis herpetiformis. Strictly from a time standpoint, it didn’t take the physician long to determine celiac was a distinct possibility, but there may be expertise and significant medical decision making involved in providing the best standard of care. Let’s take a quick look at how the encounter might level when using MDM and time. MDM: “When looking at the table of risk to select an E/M we start from left to right; with the first column being, what problems were addressed that day. Then onto the middle column to see the number of complexities and data addressed. Finally, in the third column, what are the risks associated with the condition being treated and managed,” explains Keisha Wilson, CCS, CPC, SPMA, CRC, CPB, AAPC Approved Instructor, at KW Advanced Consulting, LLC in New York City. The encounter must fulfil two of the three elements to justify that level. The diarrhea, weight loss, bloating, and flatulence count as two or more self-limited problems, but the symptoms combined with the unresolved gluten-related rash suggests one acute illness with systemic symptoms or one undiagnosed new problem with uncertain prognosis. This translates to moderate complexity. The provider ordered one test, which supports a straightforward level according to the complexity of data reviewed and analyzed element. Calculating risk is the next step. Even though the provider did not diagnose celiac disease, they did preemptively start the patient on a new diet and prescribed medication for the rash. Prescription drug management is enough to justify a moderate level of risk. Therefore, using MDM, this encounter would sit at 99214 (Office or other outpatient visit for the evaluation and management… moderate level…30-39 minutes…). Time: The medical record states clearly that this encounter took 25 minutes, which automatically translates into a lower-level 99213. Because this encounter involved a moderate level of MDM, but only a low level of time, you’ll submit this as 99214 to make sure the provider is fairly reimbursed for their expertise and quality of care. “Beware not to undersell the physician’s diagnostic ability,” warns Jan Blanchard, CPC, CPEDC, CPMA, pediatric solutions consultant at Physician’s Computer Company in Winooski, Vermont. ”Just because they can assess and decide quickly doesn’t mean it didn’t take time, practice, and hard work to develop that skill.”