How Your Section D Assessment May Impact Falls

Employ ‘post-fall huddle’ technique to determine the root cause of falls.

Falls, especially those with major injuries, top the list of key issues in the MDS-Focused Surveys. But could your resident mood interview for the MDS play an integral role in detecting fall risk or even preventing falls altogether? Some experts think so.

What’s more: “Fall prevention has clear clinical importance and organizational relevance in that adverse falls (i.e., falls that trigger emergent care) is one of Medicare’s quality indicators and is associated with increased costs,” according to the Oklahoma State Department of Health (ODH) Quality Improvement & Evaluation Service. “Including timely identification of patients at high risk for falls, as well as modifiable risk factors in the fall risk assessments is important.”

Can Depression Increase Risk for Falls?

Depression has been linked to increased risk for falls in the elderly, although the reason depression increases fall risk is yet unknown. And depression is often under-recognized and undertreated in older adults, ODH noted. Many studies have indicated a link between depression and falls, but the studies don’t agree on whether depression contributes to an increased risk for falls, or if patients who fall are at a greater risk for depression.

Example: A 2013 clinical review published in the American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23570891) confirmed that depression and falls have “a significant biodirectional relationship” in older adults. Researchers discovered that excessive fear of falling, which is frequently associated with depression, also increases the risk of falls.

This is because both depression and fear of falling are linked with gait and balance impairment, according to the study. But managing depression in fall-prone older adults is challenging, because antidepressant medications can actually increase fall risk and fragility fractures.

Nevertheless, the link is clear, and “continuing depression screening in conjunction with fall risk screening tools may help identify more individuals at risk for falls,” ODH suggested.

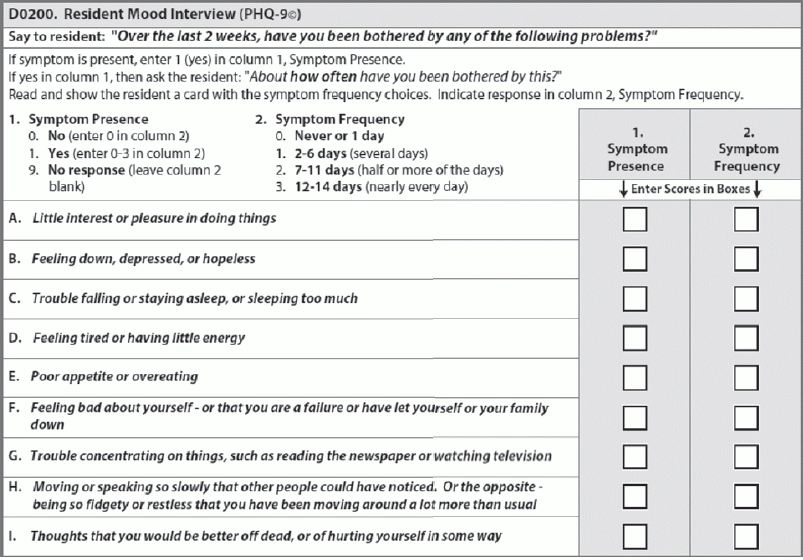

The primary area of the MDS where you can screen for depression is in Section D — Mood, specifically in Item D0200 — Resident Mood Interview (PHQ-9©). You must attempt the resident mood interview with all residents who are able to make themselves understood at least some of the time.

Heed Expert Tips for Conducting the Resident Interview

Conducting the resident mood interview isn’t always easy, especially if the resident has difficulty communicating or simply doesn’t want to talk about his feelings. Make sure the resident can see and hear you clearly, and be sure that you conduct the interview in a quiet, private setting, advised Shirley Boltz, RN, RAI/Education Coordinator for the Kansas Department for Aging and Disability Services (KDADS), in a Jan. 14 educational session.

Remember: Item D0200 has a 14-day lookback period that may include the preadmission period for newer residents, Boltz noted. You should conduct the interview preferably the day before or the day of the Assessment Reference Date (ARD) for accurate, timely coding of answers.

Here are some essential tips and techniques to complete the resident interview for D0200:

o “What do you mean?”

Summarize long answers. If a resident gives you a long, detailed answer to an interview item, use the “echoing” technique — summarize the resident’s longer answer, and then ask him which response option best applies.

Break down longer questions. If the resident struggles with longer interview items, separate the item into shorter parts and provide a chance for the resident to respond after each part, ODH suggested. This technique of “disentangling” is especially helpful for residents who have moderate cognitive impairment but can still respond to simple, direct questions.

Allow the resident to respond any way. Keep in mind that the resident may respond to questions verbally, by pointing to answers on the cue cards, or by writing out answers, or any combination of these methods.

Consider a ‘Post-Fall Huddle’

In the event of a fall, many acute care settings have a practice of conducting a “post-fall huddle.” This is “a brief meeting occurring immediately after a fall that includes staff caring for the resident and the resident himself/herself (if applicable),” noted Katy Nguyen, MSN, RN, QIPMO Educator with the University of Missouri Health System Sinclair School of Nursing in a recent tutorial.

“The purpose of this practice is to guide critical thinking about the event of the fall to discover the root cause of the incident,” Nguyen explained. “During this process, the team comes together immediately after the fall to observe, assess, and create or revise a fall-prevention plan.” (For a sample post-fall huddle worksheet, see “Use This Handy Worksheet For Your ‘Post-Fall Huddle’” on page 18.)

If you want to form a post-fall huddle team as part of your fall prevention program, Nguyen offered the following elements to consider in forming a team and effectively conducting a post-fall huddle:

Follow up. The interdisciplinary team should provide crucial follow-up care to ensure staff are carrying out the care plan and implementing the interventions.

o “Tell me what you have in mind.”

o “Tell me more about that.”

o “Please be more specific.”

o “Give me an example.”